Fritz Maurer

“You can try to preserve traditions—but not culture, because it changes,” says Fritz Maurer, a native of Switzerland who settled in Bhutan 45 years ago. He’s a resolute gentleman, 74 years old, and dressed in a traditional Bhutanese Gho. His wife Rinzin Lhamo, a native of Bhutan, died five years ago. They have five children together.

Maurer was 29 years old and living in Bern, Switzerland when he spotted an ad in a Swiss newspaper from the Kingdom of Bhutan seeking its first steps towards modernization. A cheese-maker by training, Maurer moved to Gogona, Bhutan to help implement new dairy processing techniques. Maurer immediately fell in love with his new surroundings. “When I came here,” he remembers writing to a friend in Lucerne, “I didn’t feel like a stranger.” He claims to have never used his return plane ticket.

“When I came here, I didn’t feel like a stranger.”

Maurer set to work revolutionizing cheese production in Bhutan. “They had cows, but they didn’t have any surplus milk,” Maurer explains. Up until then, any milk production in Bhutan was limited to personal use. “It was like Switzerland 200 years ago.” He began introducing concepts of cattle breeding, silage and other feeds, a commodities market and cheese processing. He set up two cheese factories as part of a Swiss-Bhutanese joint project.

The same year he arrived in Bhutan, Maurer became friends with the King’s brother, Prince Namgyel Wangchuk, a strong supporter of managed development and almost exactly the same age. Encouragement and trust from the prince were instrumental in driving Maurer’s efforts and overcoming challenges along the way. “We had nothing to start,” Maurer recalls. “The only way to communicate was tap, tap, tap Morse code, and now I have a Nokia.”

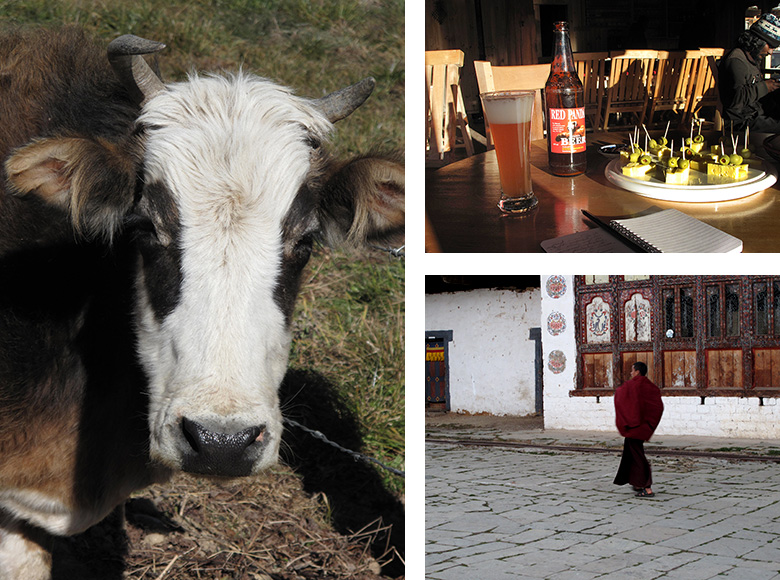

Unsatisfied with cheese alone, Maurer soon branched out into various other modernization initiatives. Bhutan’s apple surplus in the 1970s inspired Maurer to purchase two large cider presses from Switzerland. In April 1977, he was appointed as the District Agriculture and Animal Husbandry Officer. Maurer also introduced beekeeping to Bhutan in 1986 and established a brewery in Bumthang in 2006, producing a popular brew called Red Panda.

The tension between preserving tradition and fostering modern development does not produce any nostalgic regret for Maurer. “Raincoats were made of Yak wool, very warm and dry, but oily, and now the Yak is used to make bed covers,” he explains. Maurer’s insights reflect how Bhutan has maintained its cultural mores and traditions alongside modernization. “We want to keep the [fiber] spinning, the old ways of making tea, herbal medicines. We can still learn from them, but it’s expensive,” Maurer ruefully observes, “So maybe you don’t need some things, but sometimes you give up quality.” Yaks are still integral to Bhutanese artisanship.